“If we knew what it was we were doing, it would not be called research, would it?”

― Albert Einstein

The more I think about it the more I see that the process science, particularly psychology, uses may be flawed, but at the end of the day the result is still good.

Psychology, and arguably the other sciences in some experiments, is a field where through experience and thinking about things, you can often arrive at the same answer as a long and expensive experiment, but where that experiment still tells you nothing with certainty. I have noticed that in psychology, we have these theories, that in a sense guide our investigation of individuals, but we don’t necessarily use to know anything. Probably a by-product of the number of studies that are correlational in nature. Even when they are experimental, we come up with these cool results, but rather than proclaim them to the world, we downplay them and say, well they might not generalize, outside this setting, or we might have missed some other variable.

In a sense this almost seems to be a field aimed at confirming intuition. Of course, especially when it comes to mental illness and understanding how to best treat them, human instinct has come up with some pretty bizarre ideas. Some pretty damaging solutions. Does this mean that as a field it is flawed? No. Sometimes even science science gets it wrong (drug companies I’m looking at you).

There is always room for improvement.

Perhaps because of the nature of evolution and development? We are finding new answers not because our science was flawed but because humans have changed – our environment, physiology, work habits, mating practices – we are qualitatively different from the generations before us, and will be different from the ones that follow – with development comes new issues and old issues die off. Before the invention of cars, drunk driving wasn’t a problem, before medicine advanced allowing us to live longer, many of the problems of old age, such as dementia, were never experienced.

I have read articles exploring the idea that if our DNA is 99% identical to the apes, and we are classed as a different specifies, at what point while man kind again be classed as a different species. It is easy looking retrospectively at skeletons and say, their skeletons and tools look different. But our sizes and shapes have changed as a result of our sedentary lifestyle – I am quite sure hundreds of years from now, if anthropologists dug up our bodies, they would find a species with a c-curved spinal shape from our poor posture and tendency to look down at our phones – would they class us as the first of a new species? Would my grandparents be classed as homo sapiens and I as homo praesent (somewhat funny, apparently the Latin word for phone, is almost the same as “present” oh the irony…either that or Google translate is having a laugh because other sources told me the closest word is telephonatus)?

Just a thought.

So our tests might be wrong, that’s going to have to be okay, there’s not much we can do about it. Want to know how we validate our new tests? By measuring correlation with the old test, which we are now arguing was missing something. So we’re making sure this new test is good enough by making sure it lines up with the flawed test.

But let’s say this works, eventually you get back to the original test, how was that test validated? Everyone agreed? Given the amount of controversy in the field, and the fact that each new test is developed because the authors argue that the old measure isn’t good enough, I find this highly suspicious. There are literally hundreds of tests of depression. Hundreds. Of course it’s not that straight forward – we add in the idea of incremental validity, it has to predict something else. For scientists to accept a new measure there has to be something it adds – incremental validity, otherwise what’s the point. But the incremental validity seems no more valid than the idea of convergent validity supporting the validity of a test.

But let’s say this works, eventually you get back to the original test, how was that test validated? Everyone agreed? Given the amount of controversy in the field, and the fact that each new test is developed because the authors argue that the old measure isn’t good enough, I find this highly suspicious. There are literally hundreds of tests of depression. Hundreds. Of course it’s not that straight forward – we add in the idea of incremental validity, it has to predict something else. For scientists to accept a new measure there has to be something it adds – incremental validity, otherwise what’s the point. But the incremental validity seems no more valid than the idea of convergent validity supporting the validity of a test.

Many of these measures involve issues of clinical concern, say for example depression. If the previous measures were used to make diagnoses, and the diagnoses are used to form the groups to be compared in validating the discriminability and general validity of the new measure – how do we know that the previous measure wasn’t so flawed it misdiagnosed. Now your results are impacted by the inaccuracy of your groups. Yet we assume that this is not the case, we may be perpetuating diagnostic and measurement flaws.

At this point I really just seem to be a trouble-maker, raising issues without truly acknowledging the benefits and solutions.

So allow me to flip the coin.

Our measures are potentially flawed so why use them?

Because we need some way of understanding – so we generate tests aimed at capturing the generalities of the disorders, and we make ourselves aware that an atypical presentation is possible. Maybe the new tests are because we have learned more and we are trying our best to include all the specifics we know. The measures may be flawed, but at least they tell us something. To know nothing is terrifying and useless. Identification is the first step in treatment, not the last, so if our measure was flawed, the individual may not get the diagnosis, but they can still have the help. If they were diagnosed, essentially their treatment will be no different, except in cases where medication (i.e. antipsychotics for schizophrenics, or lithium for bipolar) is needed. Basically? We have to start somewhere.

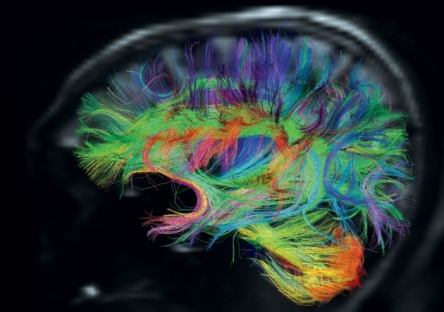

Where do we start? With our understandings and interpretations of human behaviour. We cannot do like the theoretical physicists and think about our subject matter until the answer dawns on us (we we can but we have to have something to observe directly to spark our thoughts). While we have an intimate connection with our subject matter, which could afford us access to more information, we are in a sense studying variations of ourselves. But we don’t necessarily understand our own mind, how are we to claim we understand the human mind – its functions, processes, limits, flaws, and potentials? The layman bases his understandings of others minds on how he would process the information, he doesn’t necessarily understand his own mind, but he uses his potentially flawed understandings to believe he understands the minds of others.

Psychologists adopt a much more rigorous methods, but we cannot completely detach ourselves from the issues of the laymen. Before we throw the baby out with the bathwater, we should recognize that while we don’t always understand our subject matter, neither do scientists. Do they know what an atom looks like? No, it’s too small to observe, but based on their conceptualization (which took quite a few tries by the way), they conduct experiments and make predictions – they have no concrete knowledge of the nature of an atom, but they use the theory like it’s fact. Do they know how the heart functions completely undisturbed? No, they see how it functions through imaging techniques (which could disturb the function in some way) or through scopes or when the chest is open. That understanding is still very advanced, and so they use it in medicine. Do they always get the results they were expecting? No.

We think we understand, we sometimes do, but sometimes, we are surprised and learn something new.

As Claude tells us, it is only through being proven wrong that we learn anything.

Studying the human mind, means we will often be wrong, but we can accept this issue, because we also have the opportunity to learn/understand something – may not perfect knowledge, but for me there is no true distinction between knowing fact and believing fiction. Both depend on our appraisal of the information and our experience of knowledge and understanding. If we accept that there is no way of knowing then we are helpless to function, predict, and understand.

At the end of my seventh semester, halfway through my fourth year, do I have a solidified theory of the human mind? No, how could I? It’s much too diverse. I have theories of specific areas of the human mind but no theory can cover everything. We are too different with too many parts. And then there’s the issue of knowing more than we can explain – like knowing how to run without being able to explain how.

Life is complex, we are going to be wrong sometimes, but like I said, we have to start somewhere. I have no solution to this issue, I cannot make the measures perfect, I cannot predict much with absolute certainty. The only solution I can propose is to accept this – let it be ok to be wrong, accept that only in this moment is our explanation useful in any way. Accept that we don’t know things, but we can have ideas, it is not wrong to use these ideas. We have to start somewhere.

In my mind, if we can accept that our process is flawed and somewhat illogical, then we’re alright. As long as we accept that moving from the specific to the general isn’t exactly right, and because of that we cannot reasonably argue that our specific assumptions based on our potentially flawed generalizations, we cannot argue with absolute certainty that we are right, then we’re ok.

For a really interesting TED talk from Kathryn Schulz check out here.

“Without being sure of something, we can not begin to think about everything else.”

― Kathryn Schulz

Check out next week – Claude and I had some really interesting conversations on the brain and what it does, I’m working on some stuff, but my minds a little busy and these things are a little messy.